The subtitle of The Wisdom to Survive – Climate Change, Capitalism and Community – sets out the lofty ambitions of the filmmakers. They want to tackle those four big C-words and a dozen subtopics in a movie a little less than an hour long.

The subtitle of The Wisdom to Survive – Climate Change, Capitalism and Community – sets out the lofty ambitions of the filmmakers. They want to tackle those four big C-words and a dozen subtopics in a movie a little less than an hour long. In that time, we hear about glaciers, then the shells of plankton, then a sound bite from a sermon about the pursuit of money, then society’s impossible and false expectations, then genetic engineering, then Aboriginal water rights, then the marginalization of women in the developing world, then Occupy Wall Street, then the need for medicine people to restore balance within individuals, and so on. That’s not even half of them.

The thesis is that all these topics are inextricably linked. At about the 50-minute mark, a young woman explains that the environmental movement is connected to the food movement, which is connected to the women’s movement, which is connected to the LGBTQ movement. All of these connections are fascinating and could support an important, compelling documentary on their own. But these are deep and complicated issues, and to address every one of them meaningfully in such a short amount of time is asking a lot of the film’s subjects.

The Wisdom to Survive \ John Ankele

Maybe the filmmakers sense this, and their solution is to just have a lot of subjects. By my count, we are introduced to the talking heads of 21 people. Doing the math, each person gets an average of two and a half minutes to give a sound bite over top of B-roll footage of uneven quality.

They’re all interesting people that ought to be heard, but this just isn’t a fair format. Also competing for screen time are multiple poetry readings, a Dostoyevsky quote, an amateur violinist playing in his office Review and a composer-cellist imitating whale song. That the menagerie of messages is coherent enough to be understood, if not exactly absorbing or persuasive, is an accomplishment.

The strongest part of The Wisdom to Survive is an intermission from short stock footage clips of birds, waterfalls and oil derricks. For five minutes, the film slows down and we focus in on a man doing permaculture in Vermont. The camera follows him around gardens and rice paddies and we watch him pick mushrooms and pull up grass for mulch as he talks about his paradigm of agriculture.

This works. It isn’t that horticulture is a more interesting subject than whaling. It’s that when the permaculturist says “don’t plant a tree; plant an ecosystem,” it’s not just a metaphor for the interconnectedness of the environment, the economic system and all of humanity. He’s also talking about an actual tree. The Wisdom to Survive needed more of those real, tangible moments to bring the ideas down to earth.

Greedy Lying Bastards

Greedy Lying Bastards \ Craig Rosebraugh (dir.)

Greedy Lying Bastards makes a sharp contrast to The Wisdom to Survive. Where Wisdom attempts a thoughtful, soft-spoken reflection on all the problems our world faces, this documentary is more like a furious diatribe. Greedy Lying Bastards is precisely as subtle as it sounds. It has good guys and bad guys. The problems aren’t complicated; they’re a bunch of rich libertarians. This is Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth told in the style of a Michael Moore barnburner: lots of science and rock music.

Unlike Inconvenient Truth, Greedy Lying Bastards isn’t about climate change but rather the argument about climate change. It’s about the lobbying, the money, the rhetorical strategies and the spokespeople for climate denialists in the US.

It’s more than just an exposé of the other side though. The film also devotes much of its run time to debunking the specious arguments that are often repeated by denialists. It serves as a crash course in both what environmentalists are up against and how to fight it. The tired old talking points about volcanoes and sunspots and “natural climate fluctuations” are put to highly qualified scientists, who supply the pithy retorts and trump cards. Write them down before heading into battle.

The answer to someone saying we can’t afford to shake up our fossil fuel-based economy isn’t to argue about numbers, but to cut straight to a clip of Hurricane Sandy. That’s a cost people get. When Mitt Romney says he’ll help families instead of trying to “heal the planet,” don’t prattle on about the false dichotomy between jobs and the environment; show what happened to the families who lost houses in the Colorado wildfires.

Over and over, the message of Greedy Lying Bastards is clear: don’t let the climate change deniers frame the debate in terms of a theoretical computer model about a distant future. Climate change is devastating people right now. Islands are being washed away now. Ice is disappearing now. Droughts are wiping out crops now. This is hammered home with pugilistic editing, hard facts and smart infographics.

This kind of take-no-prisoners approach won’t be for everyone. It’s polarizing and partisan. It isn’t about creating an evenhanded, constructive dialogue. It’s for people frustrated to be losing a public relations war against a side with no scientific basis and clearly nefarious motives.

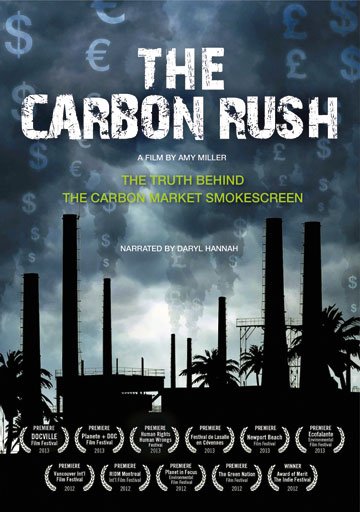

The Carbon Rush

The Carbon Rush \ Amy Miller (dir.)

The Carbon Rush is neither bombastic, polemic nor contemplative philosophy. The filmmakers are interested in the practical problems facing people in the developing world. It immediately drills down to the details, locations and people and stays there. With a slick animated sequence at the start, we learn the basic idea behind carbon offsets. Under this system, businesses accept a limit on how much their operations can pollute. Those that make an extra effort and cut back more than they’re forced to are rewarded financially with carbon credits. Those that overshoot their carbon cap have to pay up by buying carbon credits to cover the difference. After this brief introduction, Amy Miller’s film takes us to locations in the developing world to hear the stories of those exploited by this arrangement.

The Carbon Rush is a forceful documentary that shows how carbon offsets can go terribly wrong. It has become common practice for companies that want to keep polluting to invest in UNcertified offset projects in the developing world. These include renewable energy and forest preservation projects that are supposed to compensate for the companies’ excess pollution.

RELATED: The Carbon Rush book review.

Take a eucalyptus plantation in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil, where pig iron mines use charcoal made from the plants instead of some other more polluting fuel. The eucalyptus turn carbon dioxide from the air into leaves and roots and stems, which are then burned for fuel and the carbon emissions are returned to the atmosphere.

It’s true that this cycle doesn’t emit as much as burning fossil fuels, which at no point in their extraction and refinement process take carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. Yet there’s a perverse logic to making money by sucking up some CO2 and then promptly putting the gas right back into the atmosphere. Miller’s film goes into six prevailing examples of carbon-offset projects. One is a hydroelectric dam in Panama. Again, maybe it is creating electricity with less greenhouse gas, but it is also facilitating the expansion of mining operations, which need both the diverted water and the electricity that dams can supply. Meanwhile in India, a recycling industry is being displaced by massive “refuse-derived-fuel” generators that are simply burning the materials.

If the benefits of these projects are so debateable, the costs aren’t. The eucalyptus case study opens with a small roadside funeral for a man. His mother explains that the plantation’s private guards believed the man was gathering wood from the plantation, so they seized, beat and killed him. All the local people who appear in the film from different places on the planet talk about the intimidation and bullying by the companies that set these projects up.

A forest preservation project, also in Brazil, allegedly used forged signatures to get ownership of the land they are supposed to be protecting, and drove residents away with an “environmental police force” that rounds up squatters and hands out fines for gathering wood or fishing.

The same story is told in India, where vast numbers of wind turbines are erected on land that the locals say has been stolen from them. They tell of the forgery, blackmail, false arrests and lies that the multinationals use to gain control. In the Aguan Valley of Honduras, the houses have bullet holes from private security crackdowns, and two leaders of a protest against a palm oil plantation for biodiesel were shot dead in the street just before they were to be interviewed for Miller’s film.

The Carbon Rush is effective at capturing how badly some of these projects have backfired. The green movement espouses notions of social justice, yet at least some carbon offsets enable hypocrisy instead. Environmentalists emphasize that the world’s poor are the most vulnerable to climate change. It isn’t fair, we argue, that those who have contributed least to the problem should suffer the most. It seems the solution imposed on them by the wealthy can be just as terrible.

The Wisdom to Survive: Climate Change, Capitalism and Community; John Ankele, Anne Macksoud (directors), USA: Old Dog Documentaries, 2013, 56 minutes.

Greedy Lying Bastards; Craig Rosebraugh (director), USA: One Earth Productions, 2014, 90 minutes.

The Carbon Rush; Amy Miller (director), Canada: Wide Open Exposure Film, 2012, 83 minutes.

Reviewer Information

Ben is a former A\J editorial intern. He’s currently a freelance writer based in Ottawa. He tells stories about nature, science and policy.

Ben is a former A\J editorial intern. He’s currently a freelance writer based in Ottawa. He tells stories about nature, science and policy.

You might also like “

You might also like “