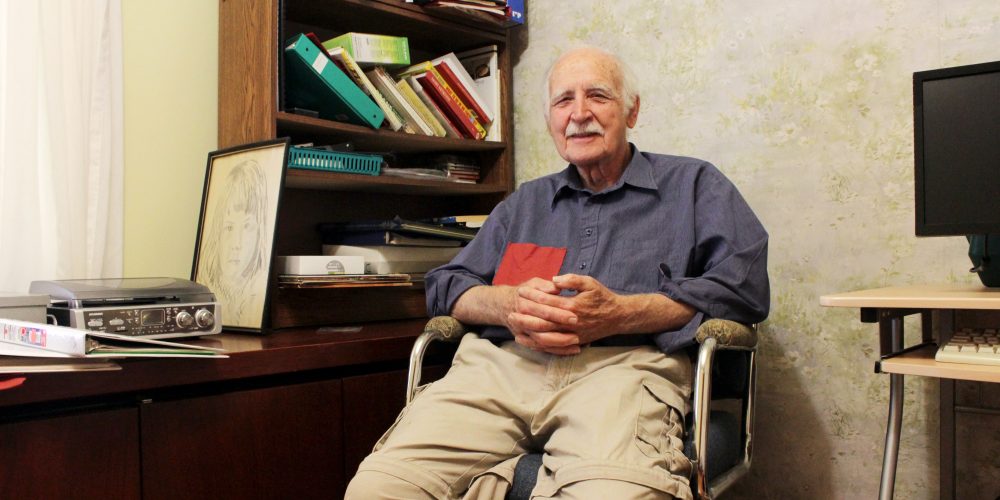

As I approached Matt Foster’s house in a Cambridge suburb, I realized that it didn’t look like the house of a political revolutionary.

As I approached Matt Foster’s house in a Cambridge suburb, I realized that it didn’t look like the house of a political revolutionary.

In fact, it was an altogether unremarkable Cambridge house: quaint and nicely maintained, but not doing much to stand out against the backdrop of the neighbourhood surrounding it. When Foster answered the door and invited me inside, my thinking continued this way: nice furniture, an expansive kitchen, but not the hubbub of activity most people associate with political movements. Foster himself was a friendly man well into his senior years, very soft-spoken and polite. Despite this, he had a firm handshake – I got the impression there was a lot beneath his surface, and I was about to be proven right.

We said hello before Foster and I walked upstairs to the room where he had been working towards world citizenship for three decades. Like the rest of the house, it was plain. Two desks, two chairs, two moderately old computers. A filing shelf filled with books and binders of notes. From this room, the organization Civis Mundi began.

Foster’s idea of a world citizen is more or less what you’d think it is. There are many problems with the world, and many of them affect the entire world. Thus, if the human race wants to effectively fix these problems, we need a way of reaching out to each other and working across national borders.

“All change comes from the bottom up,” Foster told me, paraphrasing one of his favoured quotes from Chomski.

Foster’s goal is quite literally to change the world – most people would scoff at the idea, but he gave me an example which helped translate it into practical terms.

There are many international activist groups, Foster reasons, but there are also many groups who also work within a single country only. National focus can help a lot of groups in terms of narrowing down their actions, but it can also mean a lot of repetition is necessary for worldwide progress.

“It’s all fine and noble, but they’re working within a single nation, within a single legislative process,” Foster said.

If Canada wants to outlaw the production and sale of an environmentally hazardous substance, for instance, then all the effort to get that through Canadian legislation will need to be repeated for dozens of countries around the globe. It only makes sense for the world’s people to have some common banner under which to unite and speak up in favour of positive change.

That’s where Civis Mundi comes in: the organization presents 26 fields of problems (ranging from plastic particles in the world’s oceans to democratic voting reform) with the world, and some ideas to get started on a solution. There is no membership application process, and there is no card to carry. The most identifiable trait of a Civis Mundi member would be a tie or sewn-on pocket coloured terra cotta – the group’s signature colour, readily available in any country, and Latin for “burnt earth.”

Citizens could introduce themselves as John Q. Public, Civis Mundi or say “Civis Mundi Sum” (“I am a world citizen” in Latin), in order to signify their commitment to international communication and progress.

Communication is the name of the game in Civis Mundi. Foster specifies that he wants people to talk to each other and figure out problems for the unique ways world problems affect each country. Given the advancements in international communication in the last 10 years, Civis Mundi’s goal is more attainable than it has been at any previous point in the organization’s history.

“I don’t think this would’ve been possible without the changes in communication,” Foster said.

Foster’s mission to build Civis Mundi has been a long and mostly invisible one (it’s a safe bet to say the average reader will not have heard of his cause before reading this article). He dropped out of high school in grade 10, joined the military, and served in the UN forces in Egypt. Upon his return, he finished high school, then studied unsuccessfully at Conestoga and Waterloo before finding an opportunity to work as a poultry incubation engineer.

The Civis Mundi logo.

“Poultry incubation was my passion. Going to work was like working on a hobby you loved,” Foster recalls.

As part of his work, he travelled internationally to see the newest technology and techniques for poultry incubation. Foster’s travels took him to China, India, and many countries in Europe.

“China had just opened up – everyone was still wearing their Mao suits.”

While in India and China, Foster could not help but notice how poverty-stricken some places were. He would walk by people whose shelter was a plastic bag stretched across two sticks in the ground, then go back to his marble-floored hotel.

Something had to change.

Foster initially founded the group with some of friends and colleagues, to modest initial success – most notably the hosting of Dutch professor Paul Lucardie during the early 1990s for a series of speeches in Cambridge and other Ontario towns about proportional representation, a topic back in the news today. Foster was able to accomplish this as a gesture of faith from one nation to another, and there were many other, smaller community events in Cambridge where Civis Mundi has a presence.

While I would like to say the future looks bright for Civis Mundi, as we move into an age of global information and communication, that would not honestly be the truth. Foster is aware of the elephant in the room: given the sheer scale of what Foster wanted to do, progress is tough to measure and even tougher to make.

“At my age, if I write to university papers, I’m ignored,” said Foster.

“If I write to environmental groups, they’re swamped. There is seldom a chance for conversation.”

And there is the matter of Foster’s age; he’s no spring chicken anymore. Civis Mundi’s website (civismundi.net) could use an update. Frankly, he could use some help ensuring his vision of world citizenship and an aware global population is seen by more – which may be more likely than you’d think, given how much the millennial generation prioritizes global communication and citizenship.

The difference one man or woman makes is more than likely going to be felt by people in that person’s community rather than around the world – so doesn’t that make the whole idea a wash?

But, then again, that’s all Civis Mundi wanted to do: encourage global citizens who are making positive change. If that happens to be on a community centre stage instead of the world stage, so be it.

Jack Parkinson is a graduate of Conestoga College’s print journalism program, having received his diploma in 2015. During Jack’s time at Conestoga, he contributed print and video stories to the school’s newspaper, Spoke, and worked behind the scenes liaising with advertising clients. Jack brings a grounded, realistic, and easy-to-understand perspective to environmental journalism, and he always aims to make his writing relatable to the common man.