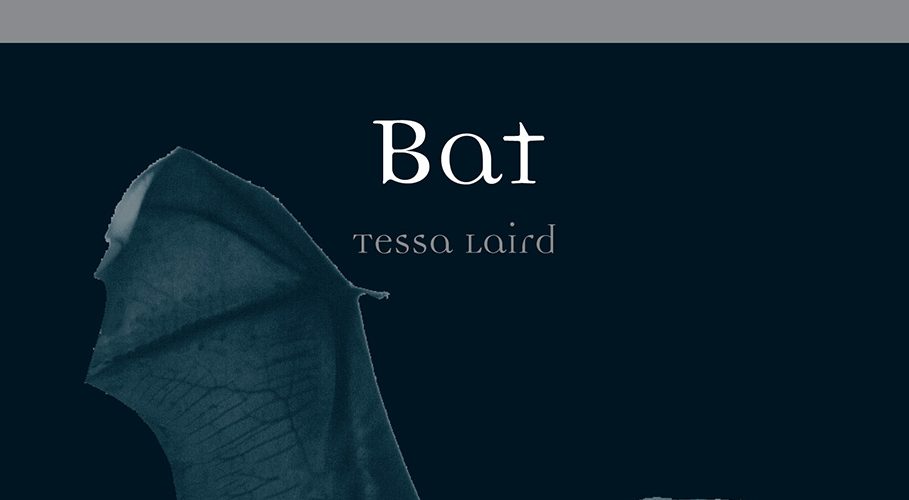

Did you know that the collective noun for bats is a “cloud”, or that in the first scientific classification of mammals, bats were placed close to humans because, like us, they have two nipples? The book Bat, by Tessa Laird, is full of similar tidbits that you will want to share with others. It is also engrossing, eloquent and beautifully illustrated.

Bat contains hundreds of delightful bat facts, but they are so grounded in context that the whole is much more than the sum of its parts. One cannot help but become intrigued and eventually transformed. I know I will never look at bats the same way again.

The author moves between Chiropteran (the scientific name for the bat group) biology, conservation, history, psychology and pop culture to capture the essence of bats, not only in all their marvellous diversity, but in our collective imagination.

Because their flight is erratic, bats are used as a symbol of insanity. Because they hang upside down and are active at night, bats can imply an inversion of normality. Their triumphant daily emergence from their caves can even represent rebirth.

And just when you think that this book is about bats, it flips perspective and shines a light on humanity and our own foibles.

Bats suffer from not fitting comfortably into familiar categories. In Aesop’s Fables, the bat switched allegiance in the war between birds and beasts, so that when it was over the bat was shunned by both and forced to live at night. Their apparently hybrid nature was first noted by the Comte de Buffon in the 1780s when he wrote that the bat is an “imperfect quadruped and a still more imperfect bird”.

Early Christian iconography used bat wings for demons, to contrast with the bird wings that we see on angels. This may have something to do with the European prejudice against bats. When a sailor from Captain Cook’s Endeavour saw an Australian flying fox for the first time, he ran back to camp terrified, claiming to have met a real live devil.

Bats have been misunderstood throughout human history. It is, on reflection, extraordinary that we still use the phrase “blind as a bat”, knowing that they catch insects on the wing in the dark. Echolocation was not discovered until 1938, and because we cannot hear their calls, we did not know that bats basically spend their lives yelling at the world.

Even now, few people realise that bats are socially sophisticated; they share food, information, and maintain lifelong friendships within their colonies. They even engage in oral sex!

Yet bats are celebrated in some cultures. In China, bats are a symbol of luck, in part because the words “bat” and “luck” sound like each other in Chinese. They are also beloved in indigenous cultures from Mexico to Samoa to Papua New Guinea. Interestingly, cultures that venerate ancestors tend to love bats.

And just when you think that this book is about bats, it flips perspective and shines a light on humanity and our own foibles. Such as the second world war project to drop bats with incendiary devices strapped to them so they would crawl into the enemy’s roof cavities and explode.

Or when someone threw a live bat on stage and Ozzy Osbourne bit its head off thinking it was a toy – he was rushed to hospital for shots but apparently privately wondered if anyone would have noticed a change if he had contracted rabies.

There are pages dedicated to an analysis of the Batman superhero and his many incarnations, the Dracula story and its evolution since Bram Stoker’s publication in 1897, as well as more contemporary bat-inspired art.

For example, the 2015 installation in Federation Square in Melbourne, titled Batmania, consisted of 200 life sized flying foxes made from black plastic rubbish bags with holes burned in a filigreed pattern so that they looked like the stars of the night sky shining through. Each bat was juxtaposed with a collapsed parachute, as if to emphasise man’s inability to fly unaided. If we do not yearn for the freedom of flight, perhaps we dream of the immortality of vampires or the strength and anonymity of Batman himself.

The bad reputation bats have in the human world has not been without consequences for them. Blamed for disease outbreaks from Ebola to rabies to SARS, bats have been killed in great numbers due to fear and ignorance. Their habitats are fragile and shrinking, and it is hard to overstate the planetary implications of their demise.

Bats eat many tons of insect pests and are responsible for the pollination of some important and beautiful plants: mangoes, bananas, saguaro cactus. The conservation movement for bats has taken off in recent years, due in part to some excellent photography and a new appreciation of the cuteness of baby bats.

If you read this book you cannot fail to care more about bats, which I hope means that more people will become active in bat conservation. In the author’s own words:

As we have seen, bats have been variously associated with sexuality, diversity and sociability, combined with intuition and an ability to navigate through dark places, all of which seem like desirable qualities at the start of the twenty-first century.

This review originally appeared on The Conversation.

Reviewer Information

Susan Lawler is an Associate Professor in the Department of Ecology, Environment and Evolution at La Trobe University in Melbourne, Australia.