Canada has had its share of massive, global-scale industrial development, including the Alberta oil sands and the James Bay Hydroelectric Project. The construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1958 was one of the biggest industrial projects of its time. The US$470-million project, meant to open the Great Lakes to ocean-going vessels, required more than 14,000 hectares of prime land to be flooded and 6,500 people to leave their homes. Between Prescott and Cornwall, Ontario, there are 10 villages, some of the oldest European communities in Canada, which still lie under water.

Canada has had its share of massive, global-scale industrial development, including the Alberta oil sands and the James Bay Hydroelectric Project. The construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1958 was one of the biggest industrial projects of its time. The US$470-million project, meant to open the Great Lakes to ocean-going vessels, required more than 14,000 hectares of prime land to be flooded and 6,500 people to leave their homes. Between Prescott and Cornwall, Ontario, there are 10 villages, some of the oldest European communities in Canada, which still lie under water.

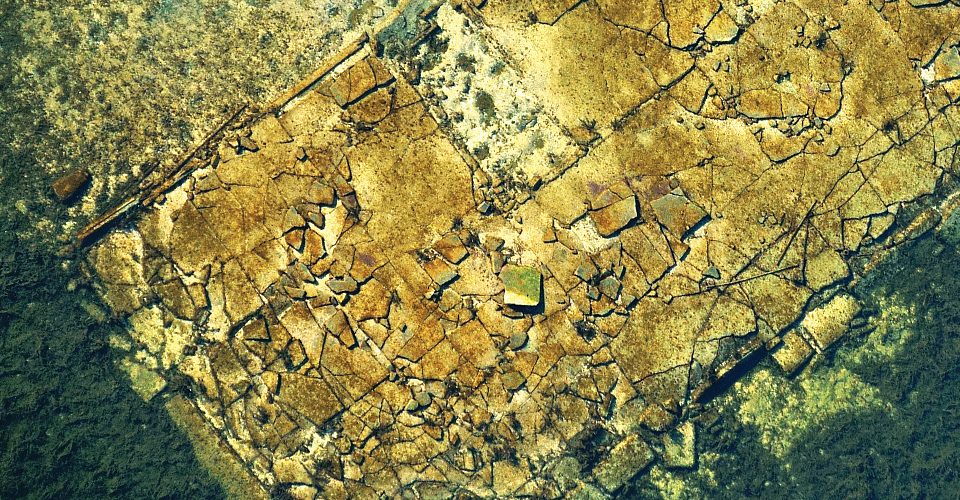

In 2009, Louis Helbig inadvertently discovered the sunken villages, and has been returning ever since to take more photographs. “In no other place in Canada have so many people had their places and spaces deliberately wiped from the map by flooding,” says the acclaimed environmental artist.

This was a largely forgotten story in the broader narrative of Canadian history when Helbig, whose art consists of large-format aerial photographs shot from his two-seater Luscombe, serendipitously spied building and road foundations from the sky. The water of the St. Lawrence was historically murky, but the prodigious water-filtering abilities of invasive zebra mussels made it crystal clear around the year 2000.

The history of human progress is often about displacement. War, famine and natural disaster are age-old vectors of forced resettlement, but industrial development has also destroyed many modern communities and caused mass upheaval. Armed with his photos and an advanced degree in economic history, Helbig began to explore mythologies around progress, flood and inundation.

“With the villages’ reappearance, it becomes clear just how much the story of the villages and their inhabitants has also been filtered,” says Helbig. He feels the official story is in many ways a historical whitewash. The idea that the residents embraced their exodus in the name of industrial progress is a now-discredited narrative of “larger national purpose … and immense social pressure to conform.”

Helbig says the lack of resistance was reflective of the times and the perceived payoff of massive industrialization. With the minor exception of a few lock operators, prosperity didn’t come to the St. Lawrence Seaway. The project literally became obsolete while being built, with tankers rapidly outgrowing facilities. The Seaway peaked well below capacity in the 1970s and has been declining ever since. Some of Helbig’s photos even depict prior attempts to open the Great Lakes to international shipping – pre-Seaway-era locks and canals that were also flooded and forgotten.

This history of unrealized promise “seems to be representative of how we operate as a country,” says Helbig. Only a handful of people became rich in the Klondike – the combined expenses of prospectors exceeded gold-production profits during its late-20th-century heyday. Helbig thinks the gold rushes, fur and timber trades, cod fishery and oil sands “all demonstrate a peculiarly Canadian ‘boom-no-bust’ mentality. We seem ahistorical and we lack the imagination or cultural fortitude to look to our past shortcomings and reflect in such a way that might avoid” similar outcomes in the future.

The Sunken Villages images themselves are subtly beautiful abstract compositions when viewed from afar and without this backstory. But look closer – at the remains of a churchyard, the foundations of downtown Aultsville, a barn and silo – and the human footprint emerges. The story of lives lived is told in footpaths worn through the woods to the fairgrounds, or in cottage lots that once had an enviable view of the river that now covers them.

Helbig first exhibited Sunken Villages at Toronto’s Canvas Gallery in 2010, the only full exhibit in an art gallery prior to this one. He limits shows to about two-dozen images because “many more become distracting and difficult to absorb.” The unique series on display in Brockville, Ontario, will also add a new twist to the project. An audio loop will play during the exhibit, composed of about 20 personal interviews with people that were either displaced from their farms or homes, involved in the Seaway’s development and construction, or both.

People began approaching Helbig after seeing or hearing about the Toronto show. A March 2012 presentation in Cornwall drew a standing-room-only crowd. One viewer explained how the imagery was cathartic and finally provided a space for processing the event. Because it’s harder to ignore something you can actually see, the luck and happenstance that enabled Helbig to capture these images has inspired many people to come forward.

Helbig hopes the imagery allows people “to think and imagine and reflect,” and that it encourages both local and national discussion about how we undertake industrial development and address conservation, and how the past can inform the future. He notes the November 1813 battle at Chrysler’s Farm, near Cornwall, in which French, English and Mohawk warriors defended against a much larger American force. He calls it “one of the nation’s most important battlefields,” where a loss would have changed or obliterated the contours of modern Canada. And it now lies forgotten and under water.

Sunken Villages, Louis Helbig. On display next at at the Agnes Jamieson Gallery in Minden, Ontario on July 8, 2014. The exhibition runs until August 23,with an opening reception and artist talk Saturday, July 12 at 1:00 pm.

This review originally appeared in Night, Issue 39.5. Subscribe now to get more reviews in your mailbox!

Reviewer Information

Janet Kimantas is associate editor at A\J with degrees in studio art and environmental studies. She is currently pursuing an MES at UWaterloo. She splits her spare time between walking in the forest and painting Renaissance-inspired portraits of birds.