The Six Nations Haudenausaunee [Iroquois] and the Anishanabee Mississaugas of New Credit (the territories of two of the founding First Nations of Canada) extend along the Grand River in Southern Ontario. In the nearby City of Brantford stands a monument to Captain Joseph Brant / Thayendanegea [1742-1807] whose vision facilitated all of these settlements.

The Six Nations Haudenausaunee [Iroquois] and the Anishanabee Mississaugas of New Credit (the territories of two of the founding First Nations of Canada) extend along the Grand River in Southern Ontario. In the nearby City of Brantford stands a monument to Captain Joseph Brant / Thayendanegea [1742-1807] whose vision facilitated all of these settlements.

The story of how this memorial was erected in Brantford’s central Victoria Square in 1886 is a poignant reminder of the intimate understanding some of our ancestors had about what is required for healthy and sustainable relations. It suggests an alternative path than that which was taken with the 1876 Indian Act of Canada and the subsequent violent history surrounding the residential school system.

While the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s concluding 2015 report urges Canadians to come “to terms with events of the past in a manner that overcomes conflict and establishes a respectful and healthy relationship,” the symbols of the Brant Memorial take us back to another sense of what it means to reconcile Indigenous-settler relations and our relationship with creation in times of climatic change.

Joseph Brant memorial in downtown Brantford, Ontario. Image courtesy of http://www.uelac.org/

At the centre is the towering presence of Brant, a Mohawk born during the spring hunting season of 1742 along the Cayuhoga River in present day Ohio. His mother named him Thayendanegea, “two arrows bound together.” Following his father’s death during the hunt, his mother returned with Joseph and his sister Mary to their home in the Mohawk Valley. There she married the Mohawk chief Canaganaduncha who had taken the British name Brant and was a close friend of the British Indian Superintendent Sir William Johnson. Impressed with the young Brant, Johnson secured an English education for him in a school that later became Dartmouth College. His mastery of British culture groomed him for a life that came to embody the name Thayendanegea as he intricately bound together Mohawk and British.

Though Brant was not a traditional chief, he emerged as an important spokesman in the councils of the Haudenausaunee Confederacy, eventually becoming known as a “Pine Tree” chief. The name associates him with the great white pine under which the Haudenausaunee council symbolically meets. This role followed an illustrious military career where he was involved in many battles during the Seven Years’ War that led to the 1760 defeat of France, acts that led him to become a captain in the British army during the American Revolutionary war (1775-1783). Brant’s designation pine tree tells of a time when the confederacy’s original five nations recovered from an era of internecine war and violence. According to this story, the Peacemaker came with a vision of one confederacy that joins the five nations in the same spirit as the five-needle cluster of the white pine. Under the tree’s roots, the Haudenausaunee buried the weapons of violence and separation. This symbolic act was seemingly renewed in the Brant monument’s bronze sculptures and bas-reliefs that were created from 13 melted British canons.

With the losses to the American revolutionaries, a move north from the Haudenausaunee homelands south of Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River became a better option for some who had allied with the British. Brant arranged the British Haldimand Grant of the Grand River Territory, which consisted of six miles (9.7 km) on either side of the river, from its headwaters to its mouth at Lake Erie. A new confederacy council was convened here in what is now known as the Six Nations Confederacy. Brant envisioned leasing the vast lands of the grant with British settlers fleeing the conflicts to the south. Many at Six Nations think of the Grand River as a cultural refuge, though now greatly reduced in size and subsumed in the legacy of Canada’s reservation system. It is also a place that symbolically carries a deep history of Indigenous-settler relations that we need to recover.

A Two Row Peace

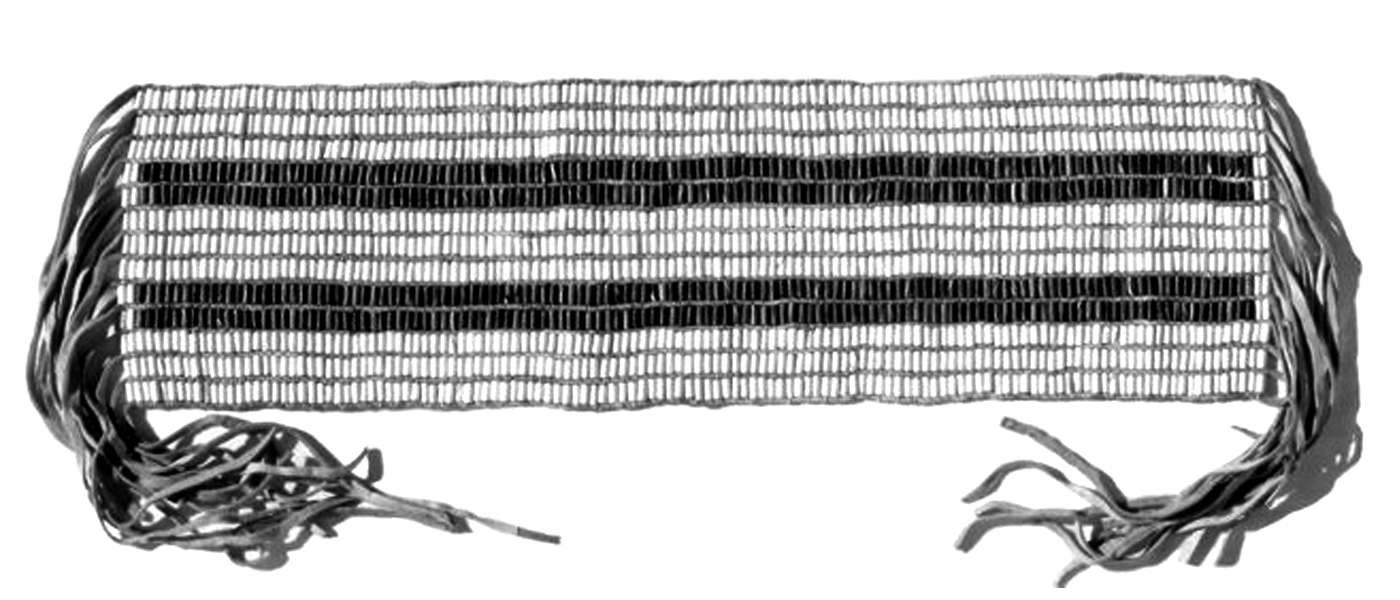

The Grand River can be engaged as a metaphor for the Two Row Wampum treaty agreements, which the Haudenausaunee have continually offered settlers since the first agreements with the Dutch in 1613, British in 1677, and even the French at the 1701 Great Peace of Montreal. On a background of white wampum are two rows of dark wampum beads that signify how the Indigenous canoe and settler ship must respect the unique ways of each other, as well as the common white waters that sustain us all. As with the white roots of peace, the natural world is the model for how we share and care for each other, this time water serving as the unifying metaphor.

We now know that the respect the settlers agreed to display was subverted by a historic disdain for Indigenous nations, which brought about much cultural turbulence.

Brant carried the two Indigenous and settler rows within him, as do many in Canada today. He came to the Grand River with the hope that the peace of the white pine and our common waters could lead to a better post-war future.

Unfortunately, the creation of the Brant memorial coincided with a darker colonial spirit that asserted itself within Canada and deeply contrasted the sharing of culture and land envisioned by the Pine Tree chief. The Canadian Indian Act of 1874 signaled a less respectful approach based on the assumption of superiority. This became wrenchingly clear in October 1924 when the Six Nations Council, dating back to the time of the Peacemaker, was forcibly disbanded. Forced community elections of a weakly supported band council swiftly followed, suspending the longstanding alliance with the British Crown. This break of the Two Row continues to this day as symbolized in the original 950,000 acre (384,451 hectares) territory of Six Nations reduced to now 46,000 acres (18,615 hectares) – a baleful legacy that has led to Brant being a figure of mixed feelings for many Haudenausaunee. The hallowed relations heralded by the Brant Monument devolved into a modern day engagement with a Canadian government that now only loosely acknowledges its debt to the Indigenous canoe.

The Two-Row Wampum Belt was first used as a record of the first treaty between European settlers

and the Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island. 2013 Marked the 400th anniversary of this treaty.

Visit honorthetworow.org for more info

A Renewable Ceremony

Despite the emerging colonizing atmosphere in which it was born, the unveiling of the Brant Memorial offers us ceremonial insights on how to heal current Indigenous and non-Indigenous relations with each other and creation. In 1874, the Six Nations solicited Queen Victoria’s son Prince Arthur to commemorate Brant with a “fitting monument.” He accepted, and in 1884 Percy Wood created a memorial that was surmounted by a three-metre bronze sculpture of Brant with two groups of three warriors representing the Six Nations, and two tableaus of traditional implements and weapons. Chief Josiah Hill presided over the laying of the cornerstone on an August afternoon in 1886. Thus began an elaborate ceremony of reciprocity, equality and renewal in the spirit of the Two Row Wampum and white pine.

Within the cornerstone was placed two identical glass canning jars, one containing settler artifacts from Brantford (named after Chief Brant), and a second with strings of wampum and a copy of the 1784 Haldimand Land Grant from Six Nations. On October 12, 1886, the official unveiling ceremony began with a large procession led by Six Nations chiefs and community members, followed by settler guests. The figure of Brant was covered by two Union Jack flags with the lower sculptures swathed in white cloth. A series of songs and speeches were exchanged, with a concluding ode to the potential of these relations given by the Mohawk poet Pauline Johnson:

Canada, thy plumes were hardly won

Without allegiance from thy Indian son.… With red reflections from the Mohawk’s arm.

Then meet we as one common brotherhood.…

The unveiling was accompanied by cheering, Haudenausaunee war hoops and a war dance.

Standing here, reconciliation feels more like a return to “a conciliatory state” that “many Aboriginal people assert never has existed” because of the ensuing violence. Being from a different time, the Brant monument speaks of condolence rather than reconciliation. The laying of the cornerstone and glass jar offerings was concluded with Chief William Ledge leading Haudenosaunee “singing a melancholy ‘Song of Condolence.’” This healing ceremony arose during the time of the Peacemaker’s Great Law as a means for bringing the five nations to peace following violence. The burying of weapons under this tree, wiping away tears and taking up new roles is a set of protocols that seems to be woven into this monument. Recovering peaceful relations today likewise requires us to bury the weapons of the past two centuries that include the Indian Act and Residential Schools. Following the lead of Truth and Reconciliation will be central to this path that begins by reconciling relations, and then moves toward the renewal of condolence.

On a climatic scale, the modern view of creation as primarily resources for human use also needs burying, for this worldview is fueling the destruction of our common white waters and roots. In Canada, protests around pipelines, the tar sands, and climate change are being led by First Nations challenging us to reconcile a colonial history based on converting land into resources with the climatic insights of our time. A renewable energy system that transforms our relationship with the planet and each other is vital. But what the Pine Chief poses to us now is the need for Canadians to renew intercultural protocols and ceremonies for being with each other in peaceful and sustainable ways on our increasingly turbulent waters.

A time for condoling all people to the creation is upon us. We need to reweave the threads of these relations out of respect for our ancestors and an appreciation of our common histories – the good, bad and mixed. What endangers us are long-held ideas and acts that reflect a turning away from respectful relations with each other, the land, waters and climate. We need to renew a dialogue with the ceremonies and images that are Indigenous to the places we live across Canada. Inspired by the Two Row Wampum, Great Law, and “two arrows bound together,” the Brant Memorial is one special place for considering what it may mean to recover new peaceful ways of reconciling and renewing relations.

Tim Leduc is an assistant professor of Aboriginal and environmental social work at Wilfrid Laurier University Brantford. His newest book A Canadian Climate of Mind: Passages from Fur to Energy and Beyond has just been released.

William Woodworth / Raweno:kwas is an adjunct professor at the University of Waterloo School of Architecture where he teaches native culture and architecture. He has a doctorate in Traditional Knowledge from the California Institute of Integral Studies in San Francisco.