The graphic image of a Korean farmer stabbing himself to death atop a barricade at the 2003 World Trade Organization protest in Cancún, Mexico brought international attention to the plight of the planet’s small farmers. Lee Kyung Hae was a member of the world’s most important transnational peasant organization, La Vía Campesina (Spanish for “Peasant Path”).

The graphic image of a Korean farmer stabbing himself to death atop a barricade at the 2003 World Trade Organization protest in Cancún, Mexico brought international attention to the plight of the planet’s small farmers. Lee Kyung Hae was a member of the world’s most important transnational peasant organization, La Vía Campesina (Spanish for “Peasant Path”).

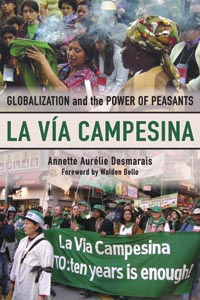

In the wake of plummeting commodity prices in the 1980s, resulting from agricultural trade liberalization, peasants and small farmers reached across borders to find allies in their fight to defend their right to grow food. La Vía Campesina, a coalition of some 100 farmer groups from over 50 countries, emerged in 1993 as a result of this outreach.

As a participant in the movement and technical advisor of the coalition since its inception, Saskatchwan farmer Annette Aurélie Desmarais has intimate knowledge of the coalition and its historical development. Based on her experience and relying on research undertaken for her PhD dissertation, Desmarais argues that corporations have shaped the global food system in such a way that there is now no international market in foodstuffs, but rather an international trade in food surpluses that are dumped into Southern markets. The sale of cheap milk, meat and cereals has undermined local capacity to produce fresh and healthy food. The only way to achieve “food sovereignty,” says Desmarais, is to take agriculture out of the World Trade Organizaton (WTO), and to press governments to promote environmental sustainability and human rights, implement agrarian reform and democratize access to other productive resources such as seeds and water.

Desmarais lays out an exhaustive chronology of meetings, campaigns and demands. But rather than bore the reader, she colours the text with the observations of participants and peppers the narrative with quotes from her interviews with the movement’s key players.

The book’s weakness is that the author positions herself as a detached observer. As she distances herself from her role as a participant, her voice sometimes gets lost in the narrative. For example, rather than bring the vibrancy of her experience into the debate on whether the WTO should be “nixed or fixed” and questions surrounding subsidies to European farmers, Desmarais summarizes these topics in a neutral tone. One doesn’t get a clear sense of where she stands on these issues.

More attention to the way that US imperialist policies have shaped the way that food is produced, distributed and consumed would have also enriched the discussion. Desmarais (or perhaps La Vía Campesina) tends to blame “Western science” rather uncritically for the inequalities in the global food regime.

Nonetheless, this book is a useful history of La Vía Campesina told from an insider’s perspective. It will be of interest to those who want to know more about the way that transnational corporations are transforming the world’s food systems and what social movements are doing to resist it.

La Vía Campesina: Globalization and the Power of Peasants, Annette Aurélie Desmarais, Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing 2007, 248 pages

This review originally appeared in The Best in Books, Issue 34.2. Subscribe now to get more book reviews in your mailbox!

Reviewer Information

Susan Spronk is a postdoctoral fellow at Cornell University and a specialist on social movements in Latin America.