Breaking News

- 3 years ago

- WHERE THE WILDWAYS ARE

- 3 years ago

- They Call It Worm. They Call It Lame. That’s Not Its Name.

- 3 years ago

- Climate of Change Episode 4: ‘Rewiring the Future’ Review

- 3 years ago

- The Playbook for Progress Homepage

- 3 years ago

- Climate of Change Episode 3: “Faith, Hope, and Electricity” – A Review

Returning to the Muskeg

We live and breathe because of this land.

Written by: Jazmin Pirozek

I sat at the water’s edge. I was looking at the plants and listening to the animals. I saw a beautiful bright purple flower. I counted its petals. The colour told me a lot about the plant—the flower collected these colours from where it lives. This colour was influenced by all the beings that live in the fen muskeg. Many of the flowers of the muskeg consume insects and build their bodies from these surroundings. The flower next to it had been fertilized and was in seed. I never noticed the shape of the seed before. I saw it was a spikey ball, appearing to have many portions making up the whole. I saw a ripened seed pod ready to release and I picked it. I pulled it open and separated the seeds. I threw the seeds into the muskeg after I took a look at them. I saw they were complete as individuals yet still part of the whole pod. I hoped to see more purple flowers in the coming months and years.

And many times, I have done this, pulled apart flowers or fertile seed pods to see of what they were made. I picked another seed in a muskeg. This one was different. This one had a strong odour, and I had an instant flash of what I was smelling. I saw my Grandpa in my mind, and I said, “Oh yes, I know this, this is what Grandpa smells like.” That wasn’t exactly it; I had no way to describe the odour, but it was familiar. I threw the opened seed into the Muskeg.

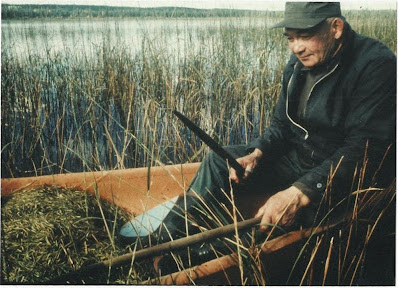

My grandfather was a Wild Ricer at Shoal Lake Wild Rice. He would spend time planting, harvesting, and preparing wild rice for commercial packaging. He planted many Wild Rice gardens in Muskeg fens on Lake of the Woods and in the lakes nearby.

I didn’t know my grandfather for long in my life. I wish I knew what he knew.

Years later, one of my advisors in university told me that he had worked closely with my grandfather. The professor was studying Wild Rice and my grandfather was his informant. He told me my grandfather knew a lot about rice. When the professor shook my hand to say that I had passed defending my Master of Science, he said to me that I have become knowledgeable about plants like my grandfather and that this was a proud day (his exact words escape me). I’ll always remember that feeling, that maybe a part of me knew what he knew; it was in my bones.

I was inspired. That smell stuck with me, so I stuck with studying the plant and its properties. It is called Acorus calamus var. americanus; my grandfather called it Wika. I learned where it lived. I learned about its neighbours. When picking it, I saw it was a woven mat of rhizomes intertwined with many other roots, reeds, and grasses into a thick humus (mud) layer. In free-flowing shallow water of fens near the Wika is the Wild Rice. My grandfather knew plants that make up the fens, bogs, ponds, and their revolution in time—this was part of his livelihood in his later years. Over time in Northern Ontario, many water bodies will fill with plants and their detritus to make an interwoven anaerobic environment that can be up to 30 feet deep. This is a natural progression of the plants of the peatlands.

The Art of the Muskeg

By Samantha Kroontje

Recent investigations into the gravesites at what were once Residential Schools have sparked an important, but painful, national reckoning in Canada. As we mourn, attempt to reconcile such an irreconcilable loss, and understand how this impacts our own personal definitions of ourselves as ‘Canadians’, we should keep in mind that we all have one collective similarity by virtue of living on common ground. Indigenous artwork – revealing history and lessons about the land we all share – grants an opportunity for Canada to connect. In this regard, John Paul Lavand is an excellent storyteller. Arresting images of dancing birds, lone wolves and mothers protecting their young reveal the lessons learned in nature. One such lesson is that people and the environment are inherently linked. Lavand’s artwork highlights the interconnectedness of all things – of wildlife and microorganisms in the peatlands, of water and land in relation to spirituality, and of our own history. As WWF-Canada’s CEO Megan Leslie would say, “nothing exists in isolation”. Soulful imagery and inspiring portrayals of our natural world expresses culture, emotion, and perhaps most importantly, shows a point of view that might not have been considered. For instance, the Ojibway don’t place the responsibility of transferring knowledge, spirituality, and epistemology solely on people. Instead, teachers can be found in the plants, animals, and land – in all living things. Art reminds us that there is more than one lens through which we can view our surroundings, while telling stories of Canada’s roots that might not be in the history books. Such stories, those written in the distinctive brushstrokes, colors, and shapes of Indigenous artwork, have the power to share important perspectives with Canadians. So now, more so than ever before, we need to pay attention to the lessons presented by Indigenous artwork to navigate these painful times and collectively build a more fair, just, and inclusive Canada for tomorrow. So, to John Paul Lavand and the creators like him who are keeping the art of the Muskeg alive, and thereby breathing life into an important national awakening, there’s only one thing left for me to say: THANK YOU!

I can pick out Wika in many water areas and I find it clearly if I see Wild Rice or if looking on water edges and marshes of deep peatlands. By observing this plant, I can see the interconnectivity of the whole of the environment. And I know that when the Canadian Shield formed, it created a foundation for the land, and when the glaciers that covered this land dried up, as our climate changed, many of the water bodies started to dry up and become glacial remnants. These remnants became the perfect ground for the plants and animals to flourish as the climate warmed. The activities of the plants and the animals made the peatlands possible. It was all the events of rocky basins, glacial warming, remnant waters and flourishing plant, fungal and animal populations together that created the peat.

Food subsistence for people and animals in the wetlands is indispensable; moose live among pitcher plants and willows, cranberries can be abundant, and all of the plant medicine is available just after thaw. The plants can live in very acidic conditions, create balance, and promote fresh water, among many other activities. We know that the ecology of a bog is a life-giving healing place. I call it the Mushkogeg—the place where many medicines grow. And Wika is one of the many healing plants that can be found woven into the top of deep mats of peat bogs.

Our food gathering is inherently intertwined with many wetland areas. Our language and food are each a part of the identity of the people. An Elder once told me that as our traditions are not practiced, the language that was used to name the practices are gone. As the bog disappears for farmland, roads, and mining, so gone is the identity of the people. We are the Muskeg; Mushkego, we are the medicine and part of the ecology of these vast differing gardens.

Colonization of the people does not only happen in the mind, but because of this cyclic interconnectivity of self and land, colonization of the bogs of Northern Ontario has also occurred. Little by little our identity is lost. It has occurred, though not only, with the entry of new populations of people after migration in the late 19th and early 20th century. Many bogs and muskegs were “filled” in to produce more “land,” spaces for the subsistence patterns of gardening, also including community access roads, hydro, and logging. Peat moss is collected and bagged today to be used in gardens to include fungal growth to promote nitrogen absorption of garden plants. As our gardens become depleted of nutrients, peat and manure are known to bring life back to the soil.

My grandfather also used the rich soils of the Muskegs for gardening. He would gently pull up some of the soil onto the shorelines to plant wild plums and vegetables. The disturbance of the muskeg can be beneficial in small increments, without large scale destruction, because it can provide more fungal bodies and some nutrients for the surface layers of soil. As well it can invite many water animals, birds, fish, and plants to spaces that have been slowly covered over time. My grandfather knew the many benefits of this kind of small-scale disturbance of wetland areas.

The detriment of the colonization of the bog muskegs has always been multifaceted. Not only is the identity of peoples slowly being lost but also the action of filling or removing peat in a large-scale industrial manner promotes the quick release of carbon into the environment. This action creates greenhouse gases, which we are genuinely concerned about as a species. The peatlands are carbon sinks, and the destruction of these reservoirs will lead to further environmental damage as we disturb habitats for mining and the slow acts of urbanization of many rural communities in Northern Ontario.

It is said that there are benefits of the economic strategies of creating industry for Northern communities. Some community organizations are invested in trading companies for resource extraction such as gold, diamonds, and rare earth minerals coming from the depths of the rocky basins of the Canadian Shield. This economic boost is two-fold; one is the organizations benefit from the increase in sale prices of stocks based upon resource extraction, and the other is that youth from the communities are educated and work in mines located in places like the Ring of Fire. Some of the Indigenous youth rely on the income supplied by the mines. We understand what is happening. The subsistence patterns have shifted.

The plants of the Muskeg are known to produce oxygen for animals while the fungal bodies breathe just as we humans do, exhaling CO₂. The Muskeg, this large being, is cyclic, many parts making its whole. I can see that the wetland is breathing, heaving with breath, inhaling, and exhaling as large beings need to do, showing us the relationship to its parts. The breathing peat stretches across Northern Ontario, West to East, beyond our imaginary borders.

As Grand Chief Solomon of the Mushkegowuk Council stated in his call for a moratorium on the development, “We are talking about the peatlands. We see them as the breathing and cooling lands for the planet, which is the third largest wetland in the world and one of richest carbon storehouses on Earth… Without the proper planning and appropriate consideration of the sensitive wetlands, much damage will occur downstream, down Muskeg, which is the homeland of the Omushkego people. We all rely heavily on this valuable and fragile ecosystem.” These lands are the identity of the people and cannot be separated.

The patterns that my grandfather lived have been replaced by a new world. On the other side, as the Muskeg is torn apart for mining and “progress,” and our youth are making a living in a colonized world, we are in the same act removing our identity for this economy, the destruction of our air and water for future generations. This is where the wires are crossed. How can we protect our identity and environment, and assure that everyone has a future in this economic world? How do we promote the healing of the Nations that live among the Muskeg lands? I don’t have any answers to these questions, but I know my heart lies in the land. It is who I am.

My personal identity is wholeheartedly tied with my relationship with the Muskeg. Our identity for millennia is the relationship with this land. We live and breath because of this land.

The Muskeg, this giant being, is made up of many relationships to its parts—it cannot be separated from my body, from any of our bodies. It is our lifeblood. It feeds, it heals, and if you do not respect the awesome nature of that being, it has no issue to swallow you whole and integrate you. Looking at the little purple flower, I got the message that the being wants to consume me, it wants me to become a part of it physically. It whispers to me, “Just a little closer so I can feel you.” I yield back because it isn’t my time yet, but it knows that I promised that when I am done with my vehicle, I will return to the Muskeg.