This series was originally posted in five separate parts, now published here together for easier reading.

This is a blog series about growth, sustainability and our planet. It is a thought experiment on whether or not the idea of a pro-growth environmentalist is an oxymoron.

This series was originally posted in five separate parts, now published here together for easier reading.

This is a blog series about growth, sustainability and our planet. It is a thought experiment on whether or not the idea of a pro-growth environmentalist is an oxymoron.

Before I begin there is one important assumption that needs to be highlighted. Everything that follows will operate on the assumption that human population growth is not exponential and we will see world population growth slow and ultimately stop before the simple number of humans becomes unsustainable for our planet. This assumption is backed up with falling fertility rates worldwide and long run projections. Many mainstream development agencies have caught on to the idea of empowering women, and how this strengthens society as a whole, including the World Bank, Plan and Oxfam. A corollary benefit of this effort to improve education and opportunities available to women is that it is shown to dramatically reduce family size. At this point, I see all conversations about the growing population as delay and diversion tactics used to avoid discussing the types of growth which actually need to be addressed.

Now, let’s get started.

Can infinite growth exist on a finite planet?

This may be the most contentious question within economics and environmentalism today. But without a proper definition of the word ‘growth’ environmentalists and economists are doomed simply to speak past each other. When economists and governments speak about growth, they are referring to economic growth, or the increase of economic value and monetary transactions. This is contrasted with environmentalists who when speaking of growth are usually referring to physical growth, or the actual amount of resources and materials that move through the economy.

For example, in 2012 Netflix saw its video service grow by 70% in Canada, the equivalent of being added to 2.5 million new homes. Now, presuming that these homes stop purchasing DVDs thanks to this new service and instead spend their saved money on non-resource based services (improvisation classes for example) the economy would see growth, while the physical throughput decreases. Or as Ryan Dyment, staunch anti-growth advocate and Executive Director of the Institute for a Resource Based Economy noted when I interviewed him: “growth can occur without any impact at all… I can stand in the street telling jokes and people can pay to listen.”

Dyment was quick to point out afterwards that this type of growth represents a very minute portion of a nation’s economy. We will take a deeper look at the real world connection between growth and resource consumption in upcoming blog posts, but at least theoretically there is no necessary overlap between economic growth and the physical throughput of an economy.

This distinction is highlighted by economists through their separation of ‘resources’ and ‘technology.’ I was lucky enough to be able to interview Yiagadeesen Samy, an Associate Professor and Associate Director at the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs, in early March, where he explained that resources in this context are basically the physical throughput, whereas technology is the efficiency with which we use these inputs. In response to the question of whether or not resource extraction was inherently tied to growth, Samy explained that while growth is tied to the use of resources, “to the extent that technology improvements are limitless, we should be able to continuously find better ways of using resources.”

And this is where the real contention between economists and environmentalists should lie. Perhaps the greatest irony is that those who practise the ‘dismal science’ of economics are perhaps the most optimistic about our world’s future. As this article by Tim Worstall shows, many economists will brush off environmentalists’ concerns about a growing economy on this distinction alone. Mr. Worstall mocks the concerns about infinite growth on the basis that theoretically economic growth could be fully sustainable and that the market could be used to manage resource scarcity. Or said in a different way: infinite growth could exist on a finite planet.

Could, not can.

Part Two: Decoupling Material and Economic Growth

In part one of this series, we discussed the fact that economic growth does not inherently require environmental degradation, at least in the theoretical world. The problem is that we do not live in the theoretical world. The world that these economic theories are trying to understand has no straight lines, no clean breaks and no simple solutions, so the question becomes: what does sustainability look like in the dirty, complicated real world?

In the very long-term, there are two basic types of truly sustainable development situations: increasing quality of life with non-material growth (but no net material growth) and zero-growth economies (no-economic growth at all). – Gilberto Gallopin

Gilberto Gallopin is the Regional Adviser on Environmental Policies at the United Nations Economic Commission and Senior Fellow at the International Institute for Sustainable Development. This quote appears in a 2011 report from the United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP), Decoupling Natural Resource Use and Environmental Impacts from Economic Growth and highlights a fundamental debate that economists and environmentalists will have to resolve if we are to continue our lives on this planet.

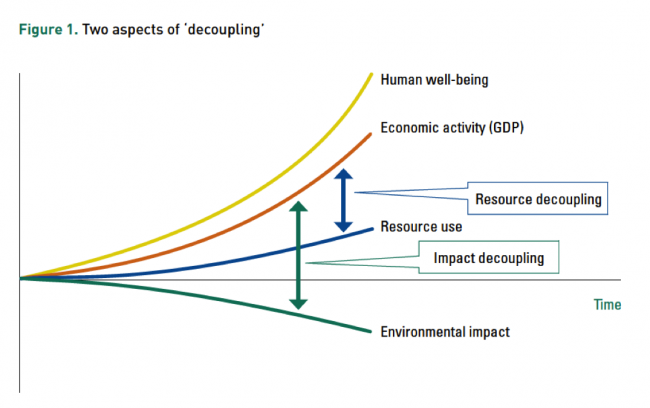

The argument that economic growth can exist in a completely sustainable world stems from the idea of ‘decoupling.’ Decoupling is the concept of removing the correlation between economic activity and material consumption (and thus environmental degradation). Put more simply, in our current economic model, making money is very much tied to selling physical things, which are made using physical resources. Decoupling is the effort to break this connection by supporting innovations and technologies that allow people to make money without using up resources and thereby harming the environment. An example of decoupling would be the implementation of deposits and bottle return in regards to alcohol in Ontario as it allows beer manufacturers to continue making profits while reducing their resource use. Here’s a visualization from the UNEP report:

Two aspects of decoupling: resource decoupling (between economic activity & resource use) and impact decoupling (between economic activity and environmental impact)

The ultimate goal of decoupling is best summarized by Gallopin:

Sustainable development need not imply the cessation of economic growth: a zero growth material economy with positively growing non-material economy is the logical implication of sustainable development. While demographic growth and material economic growth must eventually stabilize, cultural, psychological and spiritual growth [are] not constrained by physical limits.

The argument for zero-growth economies was presented to me by Ryan Dyment, executive director of the Institute for a Resource Based Economy (IRBE) and co-founder of the Toronto Tool Library. To paraphrase the full interview (available on the Green Society Campaign website), Dyment argues that it is simply impossible to fully decouple economic growth from resource destruction on a large scale, and therefore the only choice is “to develop a renewable energy infrastructure and produce goods that are designed to be biodegradable or recycled back into production.” In this scenario, Dyment argues, “GHGs can be reduced to a safe level; however, there will still be limits to growth as we align our consumption to the natural replenishment rate of the Earth’s resources (steady-state economy or SSE).”

It is not clear whether or not Dyment would accept the idea of economic growth coming from cultural, psychological and spiritual growth, or whether such growth would be large enough to warrant substantial consideration. However, it is obvious that he is profoundly skeptical of the ability of humanity to actually decouple economic growth from environmental degradation. This skepticism is shared by many environmentalists; the UNEP’s report notes that most see decoupling as simply “increasing consumption in more efficient ways.”

Externalities have a broad meaning in economics, but are most often known by environmentalists as the environmental harm that a specific economic action has that is not paid for by the person benefiting from it.

An example would be oil prices failing to incorporate the carbon emissions that burning the oil will produce – and the eventual costs that arise from increased carbon in the atmosphere.

The concern around decoupling stems from the fact that, as economies scaled up during the industrial revolution and economic thought pushed the value of free markets, growth became inextricably tied to exploiting externalities within the economic system. The most obvious immediate solution to this problem is to attempt to bring these externalities into the system and thereby account for them, such as putting a price on carbon. However, many environmentalists take exception to this, often arguing this is a lost cause because any price inherently devalues nature. For more information on this, The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB) is an excellent resource.

What is interesting about this discussion is that, regardless of whether one believes that decoupling could be effective at allowing continued growth or that a steady state economy is the only solution, the actions that need to be taken now are basically identical. Decoupling our economic activity from consumption is a necessity for either sustainable vision. A steady state economy driven by fossil fuels would not be sustainable and the same can be said of a growing economy without completely decoupled economic activity.

The sharing economy – in which Dyment’s Tool Library is a thriving outpost – is perhaps one of the most powerful and actionable movements toward decoupling. Not only does it decrease the demand for consumer products, it also frees up capital to either be invested or spent on non-consumptive services, such as massage therapy or hiring a personal trainer. In addition to this, a 100-per-cent-renewable energy grid would be just as necessary within the movement toward decoupling as it would be in a steady state economy.

The question in many ways is not what should we do tomorrow, but rather what is your house on the hill? What should we strive for in the long term? And if the conversation is about what the world thousands of years from now should look like, you may wonder why I’m making the distinction between steady-state supporters and pro-growth environmentalists (decouplers) at all. Part three will aim to explain why I advocate for sustainable growth when it is met with such skepticism by the environmental community.

Part Three: The case for continued (green) economic growth

“We’re gearing up now for the biggest struggle our party has faced since you entrusted me with the leadership…I’m talking about the ‘battle of Kyoto’ — our campaign to block the job-killing, economy-destroying Kyoto accord.”

Prime Minister Stephen Harper wrote this in a letter in 2002, highlighting what is possibly the most pervasive and damaging conception of environmentalism: that working to protect the environment is akin to attacking the economy and economic growth. This narrative has been incredibly effective and environmentalists can respond in one of two ways.

The first option is to deny the unstated premise that to be anti-economic growth is to be against human well-being and point out that GDP growth as a metric for quality of life is, at least in some ways, a sham.

Both John Coglianese, a doctoral candidate at Harvard, and Tim Nash, the sustainable economist, noted that the sharing economy presents a direct challenge to the traditional economic understanding of well-being. In our current economic model, while savings and investment are good, consumption is king. The best outcome of the sharing economy, in a traditional economic sense, would be that the money saved by sharing would be spent somewhere else.

For example, someone borrows a tool instead of purchasing one, and instead spends their money on an improv class. The improv community sees a boon at the expense of the tool industry and our GDP remains constant. However, if that money is not spent and is instead saved or invested, GDP growth would in fact decrease, even though in real terms the tool sharers’ lives have been improved with access to the goods they require and increased financial security.

This contradiction is not lost on economists. Coglianese made the point that, while GDP growth and happiness levels are strongly correlated, “it may be that the uncorrelated portion is picking up something unique that we should be giving more attention.” He went on to explain that current research seems to be pointing towards family-friendly policies, evenly distributed social standing (specifically, ensuring that social status is not heavily tied to wealth) and well-functioning communities as the most likely factors in this uncorrelated segment.

The second way to respond to the environment-versus-economy position is to defend sustainable growth. This is a larger task because it is attacked from both economic and environmentalist camps. One must defend the possibility of profitable sustainable ventures to economists (which I’ll discuss in the next post) and the necessity of growth to the environmentalists, to which I now turn.

Why is growth necessary?

This question often slips by as self evident within economic texts, but for our purposes, I believe the answer can be broken down into two parts: one in regards to ‘developing’ nations and the second for ‘developed’ (if you’ll forgive the contested terminology).

In regards to developing economies, Yiagadeesen Samy, an economic development expert, staunchly defends growth for developing nations:

“Growth is necessary for improvements in quality of life…Growth is positively correlated with poverty reduction and other important indicators such as life expectancy, education and health outcomes. It does not mean that growth will guarantee these outcomes – and this is where governments and public policies matter. But there is no question that growth is required.”

In reality, this is likely something that even the most anti-growth environmentalists would accept. There is simply no way to argue that denying the earth’s poorer nations the ability to grow their economy could be seen as equitable.

Coglianese also speaks of the inherent decoupling that occurs as an economy matures and as these nations develop we must do everything we can to reduce the environmental impact of the growth itself and expedite the decoupling of economic activity and environmental degradation. Sustainable development has been a spectacular failure thus far, but we’ve seen evidence of leap frogging in the energy industry which provides some hope.

The case for continued growth in developed nations comes directly from my discussion with Tim Nash and focuses on the necessity of debt within our current system. Nash’s basic breakdown is this: Debt is a massive part of our economy (the ecological economist Herman Daly’s estimation is that 95% of our money supply exists as debt). This debt must be repaid to the investor with interest, else there is no incentive to offer up the cash in the first place. This interest can only be made up through growth, and therefore an end to growth would leave a vast number of companies without the ability to pay back their debt – in other words, bankrupt. Mass bankruptcies would have a profoundly negative impact on society, and the concerns about lending that would follow could be even worse.

In the end, while GDP may be an imperfect metric, some form of growth will be necessary. The shift to a sustainable economy, steady-state or not, will require massive growth in the renewable energy sector for instance. With this necessity established, we move on to what sustainable growth actually looks like.

Part Four: Rent a carpet, save the world

How closed-loop systems can help us along our way to sustainable growth

About halfway through researching this blog series, I had a moment of crisis. I didn’t see how sustainable growth was possible, at least not at the scale required for today’s economy. Then Tim Nash told me about Ray Anderson, founder of Interface Carpets.

The vision of Interface is simple: To be the first company that, by its deeds, shows the entire industrial word what sustainability is in all its dimensions. Towards this vision, Interface has brought forward three innovations: two for the carpeting industry and one for industry itself.

Their first innovation was an outstanding success. Instead of selling full carpets, Interface sells carpet tiles. This dramatically lengthens the life of their carpets, as they are able to replace only the worn-out patches in areas with high foot traffic, rather than the entire floor. This increases the value of their carpets and reduces waste. It also ensures customer retention – buying new, matching tiles is dramatically cheaper than purchasing an entirely new carpet. From the success of this first innovation Interface grew, but perhaps more importantly, it became more sustainable by decreasing its impact on the environment.

The second innovation has had a stronger push-back from traditional businesses. Interface wanted to stop selling carpets, and start renting them to businesses instead. The idea is relatively simple. Instead of purchasing a carpet that lasts 10 years for, say, $10,000, the company rents the carpet from Interface for $1,000 a year. This saves the purchaser an upfront cost and provides more sustainable profits for Interface. Plus, in this business design, Interface always owns their carpets, an essential requirement if they are to succeed in their overall vision for the future of industry.

Interface’s third innovation is their commitment to creating an industrial process that completely closes the loop with its products. This means that everything that goes into making the carpets is one-hundred percent post-consumer material, and that the carpets themselves can be fully recycled back into new carpets. This would make energy the only resource consumed, so with renewable energy, the process could become fully sustainable.

So what does growth look like in a closed-loop industry?

For that, we turn to Nokia. In 2003 the Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment Directive (WEEE Directive) became European law. The law made it a requirement for all producers of electronics to make provisions for collection and recycling. Suddenly, Nokia was receiving a dramatically higher percentage of their phones back from consumers, and they saw this as an opportunity to reuse the old phones to create new ones.

Prior to this, it took Nokia approximately two minutes to disassemble a phone for reuse. To handle the increased numbers, they created a new system that can disassemble phones in two seconds. If this was a perfectly closed-loop system, Nokia’s innovation would be an example of fully sustainable growth. The company is increasing their profit (via efficiency improvements) without increasing any physical output in the economy itself.

Human ingenuity has spent centuries refining the best way to extract and consume resources in the most efficient way possible, and yet, this same ingenuity has completely ignored post-consumer waste. This is where the sustainable growth of the coming centuries has to come from – but it’s going to take some effort.

The switch to closed-loop industrial practices will not happen without regulation. At a launch for his most recent book, Waking the Frog, Tom Rand made the argument that the only path towards sustainability requires us to “change the of the rules of the game.” The WEEE Directive is a good first step, but much more is required.

There is no guarantee that human ingenuity can design closed-loop systems sufficient to sustain infinite growth. Given the fact that post-consumer products remain one of the least exploited resources of the economic system, there is an excess of room to develop and improve on the processes currently in place. We could almost certainly see such improvements build – and generate growth – for centuries, in the same way we’ve seen human ingenuity work on resource extraction in the past three hundred years.

But to extend growth infinitely would likely require a complete rethinking of our economic system, which brings us back into the theoretical realm – and is the topic for our next post. If sustainable growth is in fact a possibility, a carbon-neutral closed-loop economy is a clear early step along the way.

Part Five: Infinite Economic Growth is Possible

“Anyone who thinks we can have infinite growth in a finite planet is either a madman or an economist.” – Sir David Attenborough

This series set out to determine whether or not Attenborough is right, and to this point, it is admittedly unclear if we’ve really found an answer. Sure, efficiency improvements within closed-loop economies can create growth that does not harm the planet, but we haven’t yet figured out whether such efficiency improvements could continue ad infinitum.

This is because eventually we’re likely to reach a point where things simply cannot be improved any further. For example, if Coca-Cola decided to make its cans out of 100% post consumer aluminum, any increased efficiency within their recycling process could provide sustainable growth. But eventually, we bump up against the physical limitations of aluminum itself. It could theoretically take millennia of innovations to get to that point, but since this is an argument for infinite growth, a thousand years might as well be a few minutes.

A sure answer may be impossible, but there is still value in hashing out the possibilities. As I see it, we need to stop accepting Mr. Attenborough’s statement as unquestionable truth, and see it as betraying a fundamental lack of imagination.

If the dramatic shift to a sustainable economy is going to be realized, we must change the way growth is both understood and talked about within the environmental movement. With this in mind, there are three basic ways to understand the possible outcomes of infinite growth.

1) The economic system remains unchanged and resource limits are realized

In this scenario, growth is inextricably tied to efficiency improvements in resource consumption and at some point humanity will simply run out of ways to improve how we use things. The possibilities within this scenario range from a successful steady state economy with humanity living as a sustainable part of the biosphere, to the destruction of the earth as a viable ecosystem and the end of human civilization as we know it.

2) The economic system remains unchanged and technology improvements prove to be never-ending, allowing for infinite growth

Yiagadeesen Samy, Associate Director at the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs, had this to say about infinite growth in an interview:

“I am an optimist. I believe that humans will always find ways to do things better…there is no limit to technology. However, we need the political will to develop more sustainable policies and strategies”.

This is entirely a possibility. The world has changed dramatically in the past 200 years and there is simply no telling what could be discovered over the next 200 and into the future. But without heeding Samy’s warning, humanity may not survive on the earth long enough to make such discoveries.

3) We change the economic system

This is a possibility that sustainable economist Tim Nash brought up in his interview. It comes down to the fundamental question of what we decide to place monetary value on as a society. If there is an uppermost limit to sustainable growth within our current economic system, we could see continued – even infinite – growth by adding monetary value to more things, such as natural capital and social capital. To monetarily reward the rebuilding of an ecosystem within an economic system where biological improvement also counted as economic growth would dramatically increase the degree to which growth is possible.

Yes, this option falls well outside of conventional thinking, and no, we shouldn’t anticipate a massive shift in our economic system any time soon. However, it is important to realize that we created the economic system we have today and while we may not have a blog post from an early agrarian farmer musing about using trinkets to barter with instead of goods, that discussion still occurred and certainly had its detractors at the time.

All of that said, my aim is not to advocate for a dramatic change in our economic model, but rather to draw into focus the true nature of growth and our economic system. It seems environmentalists overwhelmingly see growth as the expansion and cementing of what we already have: more TVs, more corn, more carbon emissions – and often it is, and that needs to change, but growth should not be defined by what it traditionally has looked like.

Our economic system is not set in stone, and growth is not the enemy. Growth is humanity’s improvement at working within the system in which we find ourselves. Change the system, and growth quickly shifts from sin to savoir.

I am an environmentalist, and I believe infinite economic growth is possible and that sustainable growth is our only real hope to face the challenges that lay before us. I imagine in Mr. Attenborough’s eyes that makes me a madman, but I’m not the only one. And for someone who turned my age in 1951 he should know better than I that the world you are born into is not the world you leave behind – and sometimes it’s those mad enough to think they can shape it who are given the tools to try.