There’s no doubt that our economy has been built upon acquisitiveness. Since the Second World War, incessant growth has been based on mass production; mass production has been based on creating and channeling demand; and demand has been based on the desire to have or own. We are trained from infancy to desire new things, whether we need them or not, and to dispose of those things, whether they are worn out or not, to keep the cycle of acquisition rolling.

There’s no doubt that our economy has been built upon acquisitiveness. Since the Second World War, incessant growth has been based on mass production; mass production has been based on creating and channeling demand; and demand has been based on the desire to have or own. We are trained from infancy to desire new things, whether we need them or not, and to dispose of those things, whether they are worn out or not, to keep the cycle of acquisition rolling.

In ancient Greece, there was a special word for this behaviour. “Pleonexia” basically meant the desire to have things without regard to real need or the common good. You might say that after WWII, North America entered the Pleonexicene era.

As capitalism has stuttered recently, so has the culture of acquisitiveness. It’s not that the Pleonexicene is coming to an abrupt end any time soon, but many people are rethinking their relationship to the things that populate their lives, the businesses that provide them, and the social and environmental impacts associated with their production, distribution and use. There is a groundswell of interest in products and services that have local content, build community between consumers and producers, and involve some degree of sharing.

During the Pleonexicene, sharing has largely been seen as a painful necessity related to poverty, depression or war, or as something institutionalized by primitive cultures in ceremonies where the wealthy could cement their social dominance. But the plethora of recent books and articles about sharing suggests a resurging popular interest, and that there is nothing new or unusual about it. In fact, far from being a sign of great wealth or poverty, it’s increasingly understood that sharing has been and remains an important part of the mainstream culture.

True, some things in life shouldn’t be shared, like hypodermic needles, toothbrushes and underwear. Spouses, earphones, hairbrushes and drinks from a bottle are in a definite grey area. But many things, perhaps most, can be and are shared to everyone’s gain: food, clothes, taxis, bikes, cars, tools, hotel rooms, apartments, office space, streets, sidewalks, parks, libraries, train stations, buses, movies, books, music, stories, memories, efforts, even miseries. At the most fundamental level, we share our biosphere, including the atmosphere, soil, water and the myriad ecological processes that support life.

The Meaning of Sharing

The word share comes from old English, where it meant to divide into parts that could be distributed among a group. From this comes the common meaning of the verb – the act of giving part of what you own to someone else, as in “let’s share my pie” – as well as the derivative noun, as in “your share of the pie.” Other meanings of sharing have evolved from this root. It can mean to have something in common with someone else, whether tangible (like genetic traits) or abstract (like a philosophical belief, attitude or value). This definition eventually calved off the more active idea of sharing emotions, a secret, an experience, or information. Most recently, almost every website has a share button to propagate ideas.

While different forms of sharing all create social ties, there are important distinctions. You can share things that don’t deplete as the number of people enjoying them multiplies. When you share a story with a group of friends, you still have as much story left as when you started. These are called “non zero-sum” shareable goods. Computer file sharing is actually a positive-sum transaction in that it creates more files than previously existed. But for many things, sharing them means there will be less left for you. A candy bar, as generous children soon discover to their dismay, is a zero-sum shareable good. It’s these zero-sum physical objects and services that are the basis of the emerging sharing economy; because they are in limited supply, a money value can be attached to them and this helps regulate sharing transactions.

As the sharing economy builds steam, collaborative consumption is becoming the name of the game instead of individual acquisitiveness. In their 2010 book, What’s Mine Is Yours, Rachel Botsman and Roo Rogers describe three distinct ways of participating in the sharing economy: 1) product service systems, which facilitate the sharing or renting of a product (such as car sharing); 2) redistribution markets, which enable the re-ownership of a product (Craigslist); or 3) collaborative lifestyles, in which assets and skills can be shared (coworking spaces).

Product service systems, which is the focus of this article, have thrived with the advent of “peer-to-peer” (P2P) platforms that bring together individual owners and renters (such as room rental sites like Airbnb, or miscellaneous sharing sites like NeighborGoods), and “business-to-consumer” (B2C) services where coop, non-profit or for-profit firms rent products to members (like BIXI bikeshare or Zipcar). But it’s not just physical stuff that is being shared; it’s also peoples’ time. Sites like Kutoto (or TaskRabbit in the US) allow unemployed or underemployed people to bid on tasks their neighbours need doing (the most popular of which is assembling Ikea furniture).

The sharing economy is based on the simple fact that ownership isn’t required to get the benefits of a service or product. As some sharing proponents put it, you want the hole, not the drill. This idea didn’t start with the sharing economy, but it gradually caught on as people got used to doing such things as renting movies on Netflix and downloading music from iTunes instead of buying CDs or DVDs. We learned that we could purchase the experience, which is what we really wanted.

The sharing economy is based on the simple fact that ownership isn’t required to get the benefits of a service or product. As some sharing proponents put it, you want the hole, not the drill. This idea didn’t start with the sharing economy, but it gradually caught on as people got used to doing such things as renting movies on Netflix and downloading music from iTunes instead of buying CDs or DVDs. We learned that we could purchase the experience, which is what we really wanted.

Ownership, it turns out, is not all that it’s cracked up to be. When we own material things, we must also care for, store, clean, repair, refurbish and insure them. Indeed, many people are realizing that in some cases, the costs of ownership can outweigh the benefits. The obvious environmental advantage of sharing is that it extracts the maximum amount of use from things we already have. The more we share our existing consumer products, the less we need to mine raw materials and burn polluting energy sources to make new products, and the less waste we create.

“For a long time, we’ve preached that the only way to live an eco-friendly life is to go without,” explained Beth Buczynski, author of Sharing is Good: How to Save Money, Time and Resources Through Collaborative Consumption, in an interview with The Futurist. “Sharing increases access to the things we want and need, without the burden – environmental and otherwise – of ownership. Sharing extends the lifecycle of goods we used to use for five minutes and then put on a shelf or, worse, throw away. It’s also about forcing manufacturers to change their model, from one of built-in obsolescence to designing products that are meant to be shared, repaired and shared again.”

Sharing can also improve social equity by allowing those who can’t afford to purchase an item outright the opportunity to enjoy its use. Proponents claim that the growing number of firms fuelling the sharing economy provide both gainful employment and supplemental revenues to participating households. For example, a 2013 study found that Airbnb generated US$632-million in economic activity in New York City in one year, and the typical Airbnb host earns US$7,530 per year by renting their spare rooms or beds. Almost two-thirds of hosts say Airbnb helped them stay in their homes and more than half are non-traditional workers such as freelancers, part-time employees or students.

Sharing-based businesses and P2P sharing have flourished as online access has become nearly universal. In the past, the cost of sharing or borrowing stuff has been high because of the inconvenience involved in organizing potentially sharable resources and connecting with other potential users. The Internet and mobile devices have drastically reduced these transaction costs. Whereas sharing was once only practical within a small network of family, friends, colleagues or neighbours, total strangers can now interact online and share accommodation, tools, cars, office space, camping equipment and even home-cooked meals.

Smartphones and tablets enabled with GPS, WiFi and 4G allow people to identify nearby sharing opportunities, read reviews, arrange the share, leave feedback and make a payment, all while on the move. Modern web frameworks like Django and Ruby on Rails facilitate the creation of sharing websites. Developer tools like Google’s free Maps API make it easy for sharing platforms to integrate mapping features that help users find the nearest bike-sharing outlet or exchange spot. Large social networks like Twitter and Facebook help disseminate sharing opportunities. Sharing has become so convenient, low-risk and personalized that many products are now more of a hassle to own than to rent or swap.

The earliest of the online sharing platforms, like Freecycle and CouchSurfing, encouraged the exchange of goods and services among peers for free. But the latest sharing platforms are firmly anchored in a commercial model, mobilizing many resources that would otherwise sit idle. This alignment of self-interest with community and environmental interests is ramping up the potential of the sharing economy. A new ecosystem of individual and corporate entrepreneurs is presenting an alternative – hopefully less destructive – model of consumption. Ironically, at the centre of this new ecosystem is the ultimate symbol of reflexive acquisitiveness: the automobile.

Cars: The Gateway Drug

Québec-based Communauto was the first major car-sharing initiative in North America. As an idealistic planning student at the Université Laval in Québec City, founder Benoît Robert studied German car-sharing models and discovered their advantages compared to car ownership. Not only did car sharing reduce the number of vehicles needed to serve a given population, but paying to use a car by the hour or kilometre tended to limit the amount of driving people did and would better balance their driving with other modes of transport.

Robert used these lessons to launch Communauto in 1994. Originally he signed up 15 people to share three vehicles as a members’ coop. Twenty years later, Robert is the sole owner of the company, which has 70 employees and 28,000 members in four cities (Montréal, Québec City, Gatineau and Sherbrooke) sharing a fleet of approximately 1,300 vehicles. The cars are parked at almost 400 stations located strategically near major transit routes, catering to households who can walk, bike or take transit to most destinations but need a car for occasional use.

The impacts of Communauto’s car-sharing operations have been evaluated in two independent studies. In 2012, Louiselle Sioui and her colleagues at l’École Polytechnique de Montréal reported that Communauto members owned only 0.13 cars per household compared to 0.89 cars per household among Montréalers in general. They also found that Communauto members used a car for only one-quarter of daily trips compared to their neighbours, with the difference taken up by more walking, biking and transit trips.

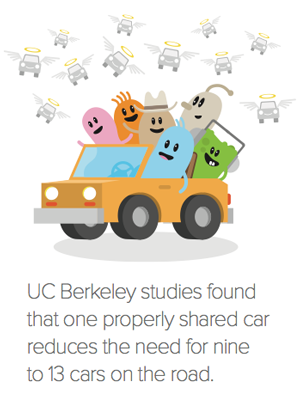

A 2006 study by Tecsult Inc. noted that nearly three-quarters of Communauto users either sold a vehicle or chose not to purchase one after deciding to subscribe to the service. Thus, each shared vehicle substitutes, on average, for eight owned vehicles, saving not only the energy and materials embedded in those vehicles, but also the parking spaces and other resources that are needed to support car ownership.

Tecsult also concluded that Communauto members reduced their annual driving by 2,900 kilometres on average after signing up with the service. Because Communauto cars are more gas-efficient than the average vehicle, the study estimated that members emitted 60-per-cent less CO2, an annual difference of 1.2 tonnes per member. The study calculated that Communauto’s fleet had reduced greenhouse gas emissions by 10,000 tonnes annually.

The company has since more than tripled its membership and introduced a number of other environmentally friendly features. A fleet of hybrid and all-electric cars that draw on Québec’s inexpensive and relatively sustainable hydroelectric power is now available in Montréal and Québec City. Members can offset the greenhouse gas emissions associated with their trips by helping to purchase carbon credits that contribute to renewable energy, energy efficiency and forestry projects in developing nations. The company, which styles itself as a social entreprise, also has agreements with the BIXI bike-sharing network and public transit agencies to offer discounts to Communauto members and encourage sustainable transportation alternatives.

Although Communauto was the pioneer in North America, numerous companies now serve cities throughout Canada and the US. Zipcar is in more than 170 US cities, plus Vancouver and Toronto. Car2Go, which is owned by Daimler AG and uses their smart car exclusively, is available in Vancouver, Calgary, Toronto and Montréal, along with two dozen other cities in the US and Europe. Most other car manufacturers are experimenting with car-sharing services to attract young customers and capture some of the growth in this effervescent industry. As of 2013, there were more than one million members of multi-city and local or regional car-sharing initiatives across North America, with almost 150,000 in Canada alone.

Another burgeoning model is P2P car sharing, in which private owners rent their vehicles to strangers. Owners log into a network and indicate when and where their car and keys will be available. In Québec, Communauto is piloting this model in a limited number of neighbourhoods, while US services like RelayRides, Spride Share and WhipCar are proliferating.

Car sharing works because the value proposition is compelling. “A new car is expensive and sits in a garage or parking spot 90 per cent of the day,” explains Marco Viviani of Communauto. “On the other hand, car sharing is affordable and convenient, especially when users can employ mobile apps to locate the closest available car and make a reservation. Communauto started before this technology was available, but it wouldn’t have lasted long without it, or would’ve stayed at a niche level.”

In the urban transportation universe, car sharing is creating a new niche in which ownership is seen as a low priority and car usage is accepted as part of a diverse transport cocktail that also includes transit, biking and walking. Cars are the ultimate expensive underutilized commodity, which makes them ideal for sharing. However, cars are also the ultimate symbol of our consumer-oriented society, which makes sharing them potentially transformative.

Neal Gorenflo, the co-founder of Shareable, a non-profit “news, action, and connection hub for the sharing transformation,” calls car sharing the “gateway drug” to other types of sharing. “Historically, cars were the vehicle into hyperconsumption,” says Gorenflo. “It looks like they could be the vehicle out of it too.”

Industry observers expect car sharing to mushroom in the coming years, and North American revenues are projected to top $3-billion by 2016. One reason is that recent research has shown attitudes toward car ownership are in flux throughout North America, especially among younger people. Gen Yers are far less likely to get a driver’s licence and own a car today than their predecessors – and those that do drive do so more sparingly. Car-selling companies are hoping this is a temporary blip related to the recession, but car-sharing companies are betting that it’s part of a permanent generational shift in tastes and spending habits. Automotive market researcher Dennis DesRosier thinks history is on the side of the sharers. “Kids don’t love cars the way their parents do,” he told The Globe and Mail recently. “Smartphones are replacing some of the social elements that a vehicle used to fill. They feel they can be socially more efficient (via text and Twitter) than having a big honking car in the driveway.”

Land use patterns in our cities are also a factor in this shift. A back-to-the-city movement is reviving downtowns in many cities, while urban planners and developers are putting more emphasis on creating compact, diverse, walkable neighbourhoods, especially near transit stations. Studies have shown that car sharing works best with stations in accessible urban settings where densities ensure a large pool of potential users. Moreover, urban centres have many walkable destinations, good transit networks and a lack of parking. These factors tend to make car ownership less necessary to a good quality of life and more costly from a personal point of view.

This trend toward more close-knit neighbourhoods has broader benefits. All kinds of sharing opportunities thrive in denser communities where people tend to live in smaller living units with less storage space. “When there are more people nearby to easily access and share cars, clothes or bikes, the service is more cost-effective and profitable,” says Lisa Gansky, a US tech entrepreneur and author of The Mesh: Why the Future of Business is Sharing. In compact neighbourhoods, “partnerships are easier to find and execute.”

Sharing Isn’t Always Easy

From undetectable levels at the turn of the millenium, the global sharing economy is now valued at more than US$110-billion, including both P2P and B2C platforms. Zipcar, whose global membership has grown 30-fold in the last 10 years to more than 900,000 registered users, was purchased by Avis last year for nearly US$500-million. Airbnb, which started in 2008 when two guys rented out an air mattress in their living room for overnight stays, now lists more than half a million properties worldwide (including teepees, treehouses and igloos) and is valued at $2.5-billion.

Although it’s growing by leaps and bound, the sharing economy does have hurdles. Sharing items doesn’t always make sense. Although there are exceptions, things that are fragile, irreplaceable, inexpensive to buy or difficult to transport are generally not ideal for sharing. And buying may still be best for heavy-use items. For example, even car-sharing promoters acknowledge that those who drive more than 15,000 kilometres a year are better off owning.

Although it’s growing by leaps and bound, the sharing economy does have hurdles. Sharing items doesn’t always make sense. Although there are exceptions, things that are fragile, irreplaceable, inexpensive to buy or difficult to transport are generally not ideal for sharing. And buying may still be best for heavy-use items. For example, even car-sharing promoters acknowledge that those who drive more than 15,000 kilometres a year are better off owning.

Then there is the trust issue. While lending your old clothes steamer to an online stranger is a breeze, lending your new car might be a little more nerve-wracking. In real-world communities, people’s willingness to trust others is guided by reputations for good behaviour. In online communities, building trust is trickier because people can have multiple identities that flit in and out of existence, and there is no grapevine to pick up rumours and assess risks.

Most sharing platforms try to address this issue through community rating systems. P2P websites like Zilok let owners and renters leave feedback about each other, and sites like SnapGoods require renters to make a security deposit. For bigger-ticket items like accommodation and vehicles, many sharing platforms offer insurance against damage or loss. For example, in 2011, after a woman in California came home to find her apartment trashed by her Airbnb “guests,” the company introduced a $50,000 guarantee to cover losses to renters (it was later increased to $1-million). Despite these safeguards, online chicanery exists and is undoubtedly dampening the growth of the sharing economy.

Another challenge is the hostility of established businesses and the legal barriers they are able to put up against emerging competitors from the sharing sector. Take, for example, the 2010 state law that makes it illegal for property owners to rent rooms for less than 30 days in New York. The law targeted illegal hotels and short-term P2P rentals through online platforms like Airbnb, Craigslist and Roomorama, which are much cheaper than New York’s regular hotels. The hotel industry, not surprisingly, was the main backer of the new law. Likewise, bus, rental car and taxi companies have petitioned governments to restrict car and ride services. Finally, as the sharing economy grows, governments are looking for ways to tax these new, diffuse forms of value creation.

Some thinkers are also concerned that large corporations are steering the sharing economy away from its original community-based social and environmental aspirations. For example, Zipcar’s new owner, Avis, has been criticized for undermining transit ridership among students by setting up on university campuses, and for offering SUVs in its mix of available vehicles. Meanwhile, Airbnb is introducing new verification procedures to ensure the identity of guests, along with new standards of service that hosts have to respect, like ensuring their guests have clean towels and sheets.

“Like so much else in the history of the web, which began as a more decentralized, bottom-up approach to publishing and communication, the corporate co-opting of sharing is already well under way,” writes Marcus Wohlsen in Wired. “That could mean the exact kind of centralized control the sharing economy’s democratizing effects were supposed to undermine. Or it could mean that sharing goes from a niche market of tech-savvy early adopters to a mainstream reimagining of consumer culture … Or, as is the case with just about everything else online, it could mean a little of both.”

Other critics have claimed that the sharing economy is replacing good jobs in regulated industries with a new class of atomized piece-workers, such as the “post-industrial peasants” who run odd jobs for strangers through TaskRabbit. In response to this criticism, April Rinne of US-based think tank and consultancy Collaborative Lab says, “this is not about ‘taking’ jobs; rather, this is about creating livelihoods and ways of generating income that didn’t exist before – a net market, so to speak. Most TaskRabbits are not ex-Monday-to-Friday, 9-to-5 employees. They are people who have skills and/but need flexible work arrangements – for example, retirees, mothers with young children and people pursuing another passion that requires a flexible schedule.”

Exponential growth, hostile regulations, jealous attention from the taxman and the indignation of established industries all suggest that the sharing economy is becoming a force to be reckoned with. While some observers think its youthful energy will gradually be absorbed into existing commercial relations as the sector matures, others think we are on the cusp of a major change in our way of meeting personal needs and how we relate to one another and the planet. One thing that everyone agrees on is that the sharing economy is not going away. It will grow, diversify and morph as the technology of sharing evolves and new opportunities for sharing arise.

Will the sharing economy introduce a new era of collaborative consumption or merely serve to soften some of the harder edges of the current Pleonexicene era? Only time, as they say, will tell.

Ray Tomalty is principal of Smart Cities Research, a Montréal consulting firm that specializes in issues related to urban sustainability. He is also an adjunct professor at the School of Urban Planning at McGill University, an A\J editorial board member and a regular contributor to the magazine.